Japanese Tattoo Meaning

apanese Tattoo Meaning is very strong and before you decide to make a Japanese tattoo, please, make sure that you have all the necessary information about its meaning. Really Loved this article by Irezumi Art UK which can be good start.

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” Symbology.

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

Rogue with Nine Dragon Tattoos

1858. Toyokuni III/Kunisada (1786 - 1864) Japanese Woodblock Print

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

TATTOOS IN MODERN JAPAN

At the beginning of the Meiji “1869″ period the Japanese government, wanting to raise its image and make a good impression on the West, outlawed tattoos, and Irezumi took on connotations of criminality. Nevertheless, fascinated foreigners went to Japan seeking the skills of tattoo artists, and traditional tattooing continued underground. There is a story that the British monarch, King Edward VII had a Japanese tattooist brought to him and had dragons put on his fore arms and then sent the tattooer to New England to have his friends in America tattooed by him as well, as a gift of good will & friendship.

Tattooing was legalized by the occupation forces in 1945, but has retained its image of criminality. For many years, traditional Japanese tattoos were associated with the Yakuza, Japan’s notorious Mafia, and many businesses in Japan (such as public baths, fitness centres and hot springs) still ban customers with tattoos.

Traditional Irezumi (an art form in itself) is still done by specialized tattooists, it is painful, very time-consuming and expensive: a typical traditional body suit (Vest or jacket, long or Short Sleeves, Long or Short Pants, and traditionally leaving an un-tattooed space down the centre of the body) can take, on average, one to five years of weekly visits to complete, showing that the person with heavy Irezumi will finish what he or she starts and can be very respected for it, and the imagery that is in a persons Irezumi can be viewed to see the aspirations of that individual.

YAKUZA'S TATTOO

SOURCE: GOOGLE.COM

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

MEANINGS OF JAPANESE TATTOO SYMBOLISM

Japanese Tattoo Meaning – The following is a brief explanation of the most frequently used symbols in Oriental style tattoo. However, the art of combining these symbols together will determine the final and individual meaning behind your tattoo piece. Make sure your tattoo artist specialises in this style, and further more, he/she has a true knowledge of these symbols, otherwise you may end up (as I have seen so many times already) carrying an “upside-down-joke” koi, representing your failure for the rest of your life.

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

RIU (Dragon)

In the west, it is a greedy, fire-breathing, cave-dwelling, and fear-inspiring creature that jealously guards its hoard. in the Japanese dragon tattoo, however, it symbolizes something very different. Oriental dragons are equally at home in the air or in the water. Usually embodying wisdom, strength and manipulating the forces of the universe for the benefit of people.

The face of the oriental dragon is generally not the face of one creature but many and can be different from dragon to dragon. The dragon can take on characteristics of animals it encounters through its life. The eyes can be of a demon, or rabbit, while the ears are those of a cow, the neck and belly of a snake, the horns of a stag and the scales of a koi. Its hands or talons are from the hawk or eagle and it has saliva and breath like perfume, a voice like the musical ringing of a copper bell or basin. The Asian dragon is usually the bearer of profound blessings. Like other Oriental tattoo designs, the choice of a dragon is generally an aspiration to the qualities of great goodness, wisdom, and power.

When a dragon is seen with colour in its scales, it is thought of as being at least 500 years old, younger dragons have not earned or developed coloured scales yet, and if the dragon lives as long as 1000 years it can grow colourful feathered wings, similar looking to the wings of the Japanese phoenix.

Dragon in the clouds

1832,Totoya Hokkei(1780–1850)

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

KOI (CARP)

Probably surprising to many westerners is the very large amount of ancient myths that surround these beautiful fish in the orient, and their elevated status there. The koi is more than just a colourful and collectible fish, it is also one of the most popular and beautiful story, myth, tale and tattoo themes, a beauty which belies its symbolic meaning. Although Chinese in origin, the koi is now widely celebrated in Japan, particularly for its masculine qualities. It is said to climb waterfalls bravely, and, if caught it will lie upon the cutting board awaiting the knife without a quiver, not unlike the warrior facing the sword.

Eventually, the stoic fish came to be associated with so many masculine and positive qualities that it was appropriated for the annual “Boys day festival” in Japan where even today colourful, streaming koi flags are traditionally displayed for each son in the family. In tattoo imagery, especially in combination with flowing water, it symbolizes much the same courage, control, and the ability to achieve goals with an understanding of life’s trials”.

Longmen Falls (Dragon’s Gate)

One theme that dates back to ancient China, where a legend tells of how any koi that succeeded in climbing the falls at a point called “Dragon Gate” on “Yellow River” would be transformed into a dragon. Based on that legend, it became a symbol of worldly aspiration and advancement.

Not all koi are headed for dragon gate, and not all koi are stoic, there are other stories. Another popular story is of a giant koi that is killing off the fishermen of a small village, only to be killed by a boy of the village making the boy a hero, often translated as “Golden Boy” is a folk hero from Japanese folklore know as “Kintaro”.

Rogue with Nine Dragon Tattoos

1858. Toyokuni III/Kunisada (1786 - 1864) Japanese Woodblock Print

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” Symbology.

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

Suido Bridge and Surugadai

Utagawa Ando Hiroshige (1857)

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

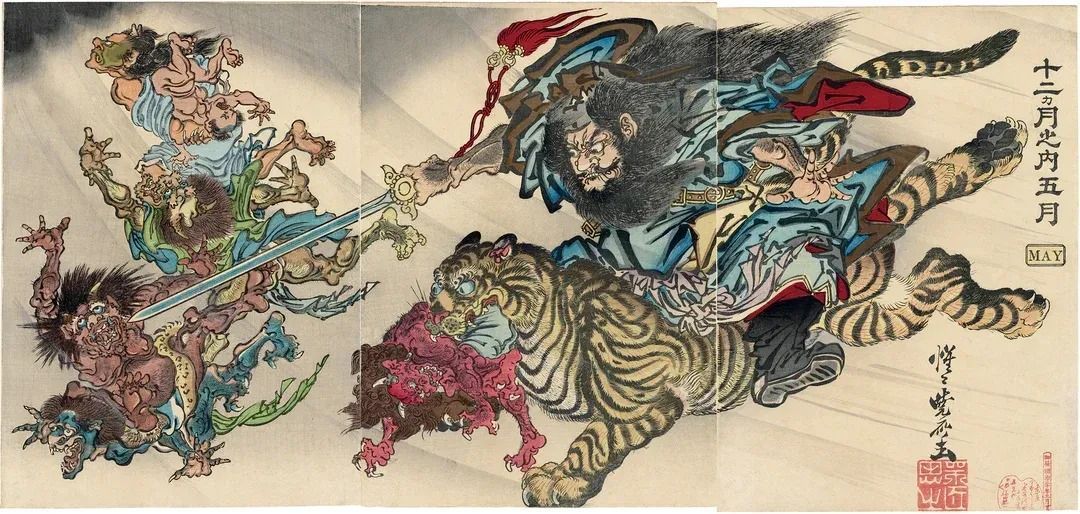

TORA (TIGER)

Considered to be the supreme of all land animals by the Chinese, representing strength, courage and long life. Tigers are also said to be able to ward off bad luck, disease and Demons. In many old prints you will see a tiger fighting demons (Oni) at the side of “Shoki” The demon queller. Tigers are one of the 4 sacred animals, symbols of the North and represent the season of Autumn and control of the winds.

Shoki Riding a Tiger and Chasing Demons

Kawanabe Kyosai 河鍋 暁斎

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

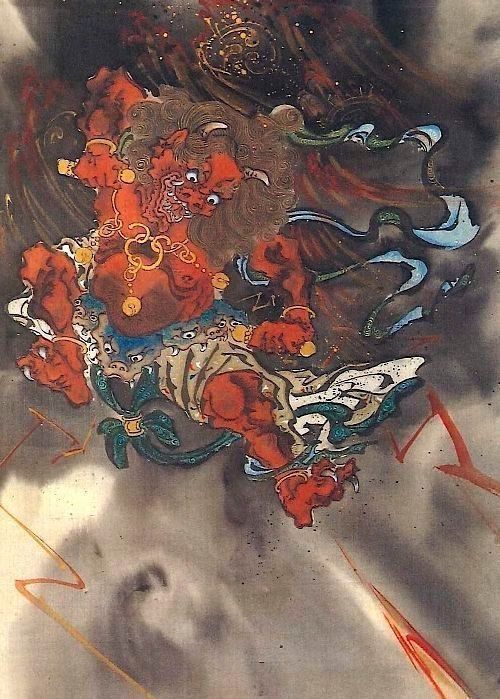

KARASHISHI (FU DOG / LION DOG)

The Foo Dog of Asia is also called the “Lion of Buddha” and that name is actually much more accurate, since it is a lion and not a dog at all. Known also as Fu Dog, Foo Dog, Fu Lion, Foo Lion, Lion Dog, Karashishi and Shi-Shi Dog. they are used extensively in Asian art, sculpture, and, of course, tattoos. But the Lion of Buddha may not be Buddhist in origin.

The local Shinto religion of Japan, which pre-dates Buddhism, also has a lion protector, with a red head, who drives away evil spirits and brings health and wealth. No matter the origin though, the Fu Lion is fundamentally protective, strong, and courageous. It is even said that when they are cubs, their mothers will throw them from cliffs, so that only the strongest survive. Many times, Foo Dogs occur in pairs, placed at gated entrances, for example, seated and yet always ready. The Foo Dog to the right is typically thought of as male, with the mouth open (to let evil out), one front paw resting on a sphere, which is often carved as open latticework and represents both heaven and the totality of Buddhist law. On the left is the female, mouth closed (to keep evil out), paw resting on a small cub, typically shown upside down on its back, which represents the earth. Often in tattoo the Foo Lion crawls menacingly, up or down an arm or leg in protection of the wearer and aspiration of heroic ability and mind.

With their pointed ears and their curly but subdued manes of hair, there is certainly a resemblance to dogs. More than likely, it is that resemblance which has caused the widespread confusion about these animals, also known as Chinese Lions and even Lion Dogs. But the resemblance is accidental and due to the fact that virtually all knowledge of actual lions was second hand to the Asian artists who initially created them. Their knowledge was second hand because, although dogs abound the world over, lions have never been native to the orient.

Lion and Cub

Utagawa Hiroshige II, 1860

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

ONI (DEMON)

The oni, or horned demon, is a popular image in the Japanese tattoo artwork of today. They are probably the most common of the ghostly beings in Japanese cosmology and are typically depicted as rampaging, violent, and cruel. Almost always shown with horns, their faces can be quite varied, similar to noh masks, and are typically pink, red, or blue-grey.

In general, oni are fearsome supernatural creatures, they have been described variously as guardians of Buddhist hell, demons who act as torturers there, carrying out the punishment given by the queen of hell to the convicted souls that find themselves being judged for the evil deeds in life. Also as pranksters, devourers of human victims, hunters of sinners, and bringers of disease and epidemics.

The gods of wind (Fujin) and thunder (Raijin) that loom ominously atop a summit of clouds are usually depicted as oni, showing that oni are not evil, but carry out duties and deeds given them by powerful deities and forces. Although fujin and raijin can be depicted using other than typical oni forms.

In many stories, Onijin is an all powerful oni that is considered a king of the oni and can be depicted as powerful, and self absorbed, but can still be over-powered by righteous forces or deities if necessary in order to re-balance an out of balance society or clan.

There is also a tradition, however, in older tales, that they can become benevolent protectors — such as monks who become an oni after death in order to protect temples.

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

HOU-OU (PHOENIX)

Probably the most important of the mythological birds, its unmatched splendour and the immortality it derived by rising from its own ashes.

Its name comes from the Greek word for “red”, the colour of fire and it came originally from Ethiopia and thought to appear only once every 500 years. In ancient China, the feng-huang bird was able to unite both yin and yang and was used as a symbol of marriage. In ancient Rome, it was stamped onto coins to symbolize the endurance of the empire.

In some versions of its story, it flew to distant lands gathering fragrant herbs which it returned to its altar, setting them afire and burning itself to ashes -rising three days later. In other versions, when the time of its death would draw near, it built a nest of aromatic twigs in which it would burn, simply from the heat of its own body. Tattooing the phoenix is done from different times of it existence, thus not always on fire! However, no matter the details of its origin, life, or death, it has become a symbol not only of the undying soul, resurrection, and immortal life but also one of triumph and a rebirth in this life.

Phoenix by Hokusai

On the ceiling of a festival float, Hokusaikan, Obuse, Nagano, Japan

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

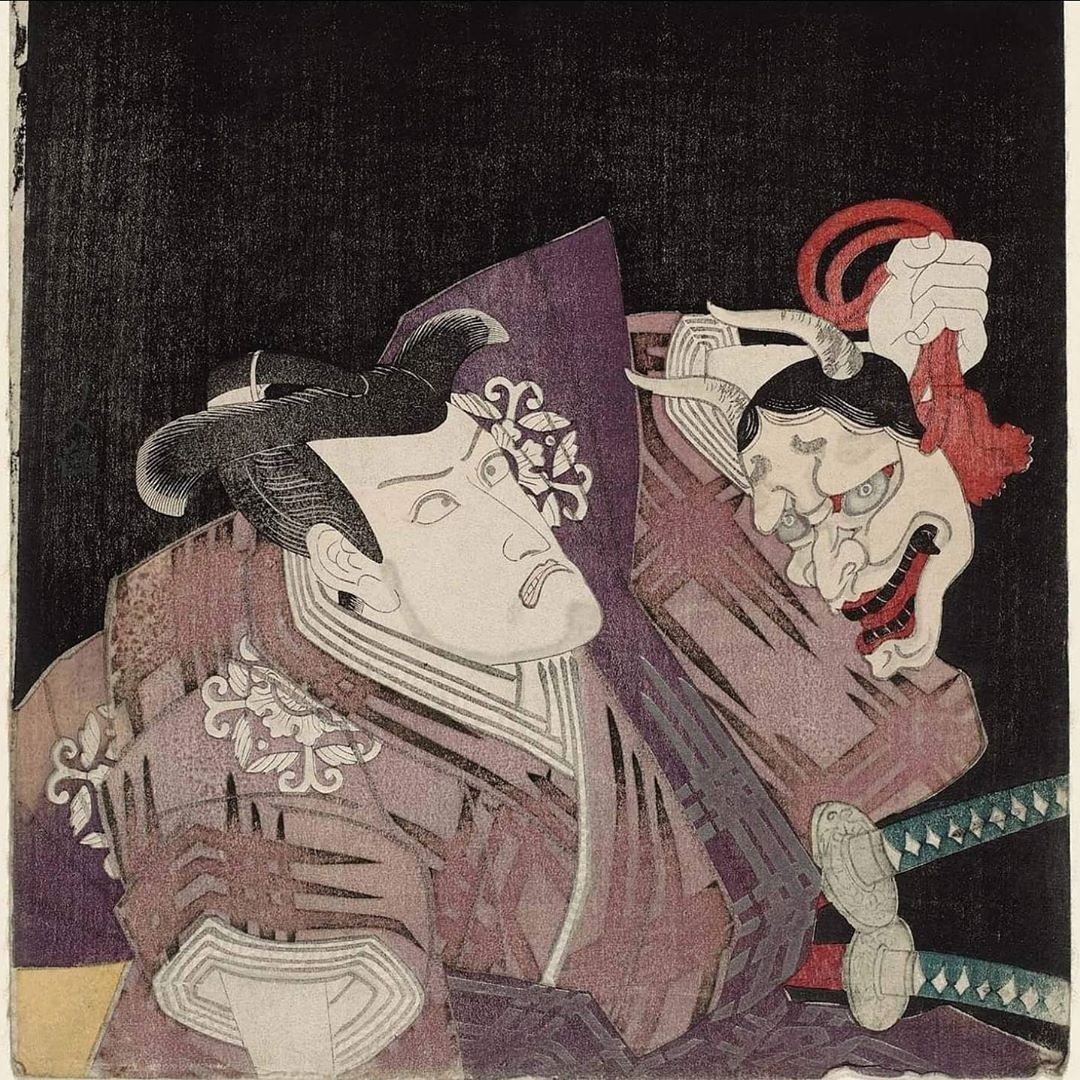

HANNYA

The hannya mask is just one example of the many different types of masks used by the traditional Japanese actors of Noh theatre. Noh performances are very stylized representations of traditional and well known stories, developed in Japan during the 14th century. The masks are used to convey the identity and mood of the various characters, who number nearly eighty in the different tales. The hannya mask is specifically used to represent a vengeful and jealous woman. Her anger and envy have so consumed her that she has turned into a demon, but with some important traces of humanity left. The pointed horns, gleaming eyes, fang-like teeth, combined with a look of pure resentment and hate are tempered by the expression of suffering around the eyes and the artfully disarrayed strands of hair, which indicate passionate emotion thrown into disorder. The deeper and more extreme the colouring of the face, the deeper and more extreme run the emotions of the character. Tattooing takes full advantage of these fanciful and engaging images, often using them in larger pieces of Japanese work or sometimes juxtaposing masks of good and evil characters. Often a Noh mask will also appear in isolation, as a work of art unto itself, not unlike the actual masks which are highly prized and very collectible. Even to this day, in Japan, a hand gesture of two index fingers sticking up from a man’s forehead is an indication that his wife is mad at him or jealous. A more reddish colour indicates strong resentment and anger and is used in such plays as Dodoji and Kurozuka, whereas a paler colour would be more appropriate for Aoi-no-ue. Dodoji is the story of unrequited love between a woman and a priest of Dodoji (temple). She turns into a demonic serpent who wraps her body around the temple bell consuming it and the priest in the process. If the teeth of a hannya are blackened in, it is to show that she would want “not” to look beautiful to anybody but her deepest love, meaning absolute targeted emotions.

There is often double meaning to all the Japanese myths. Let’s remember the role of anger! It can often be caused by despair! Long life to understanding and compassion.

Ichikawa Danjuro Vll holding a Hannya mask, Kunisada,1831

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

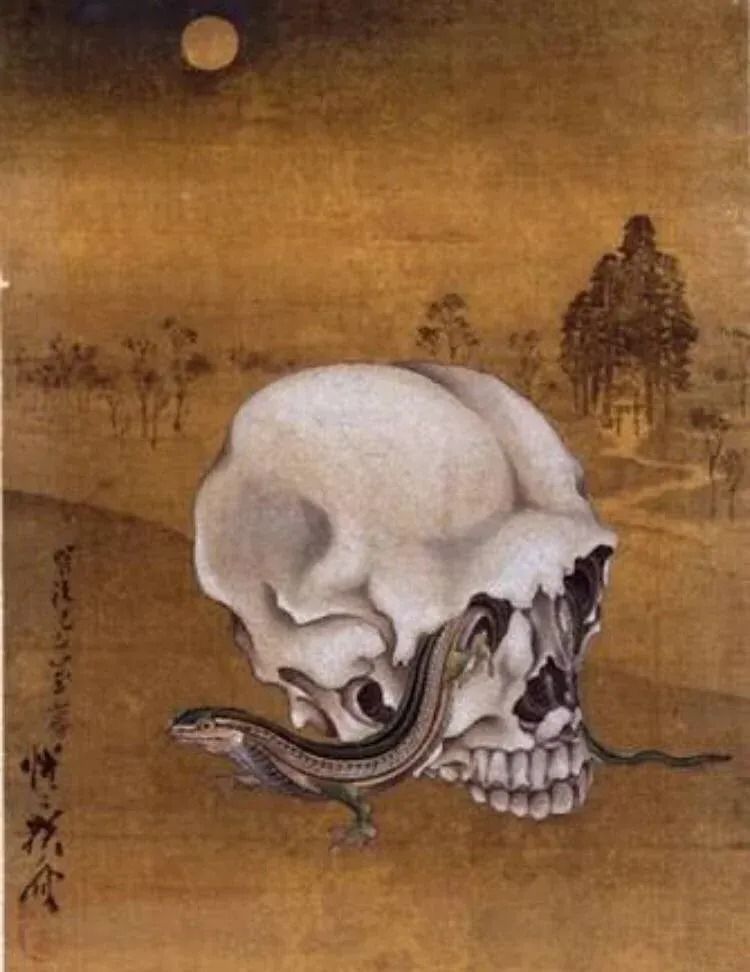

ZUGAIKOTSU (SKULL)

There is actually a more in-depth meaning to the skull tattoo designs than just anger, fear, danger or death – in fact it was not originally conceived as a symbol to represent any of these things. It was instead originally used to represent the symbol of “great change” and “celebration of a great life”. In analysing what the skull traditionally meant in ancient society we discover that it was related to the happening of great changes and an acceptance and embrace of our mortality “embracing the new”. The skull is a symbol used to celebrate and show respect for people who have passed. It’s highly probable that it’s association with death grew because of the fact that death is the greatest change that we will experience.

Today it is extremely unfortunate that the majority of the general public does not understand the true meaning of the skull, and when they see it they automatically relate the symbol to negativity. A lot of conservative people loathe the design because of its perceived meaning; however, if they were aware of the true meaning behind the design their views might be totally different.

Lizard and Skull by Kawanabe Kyosai

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

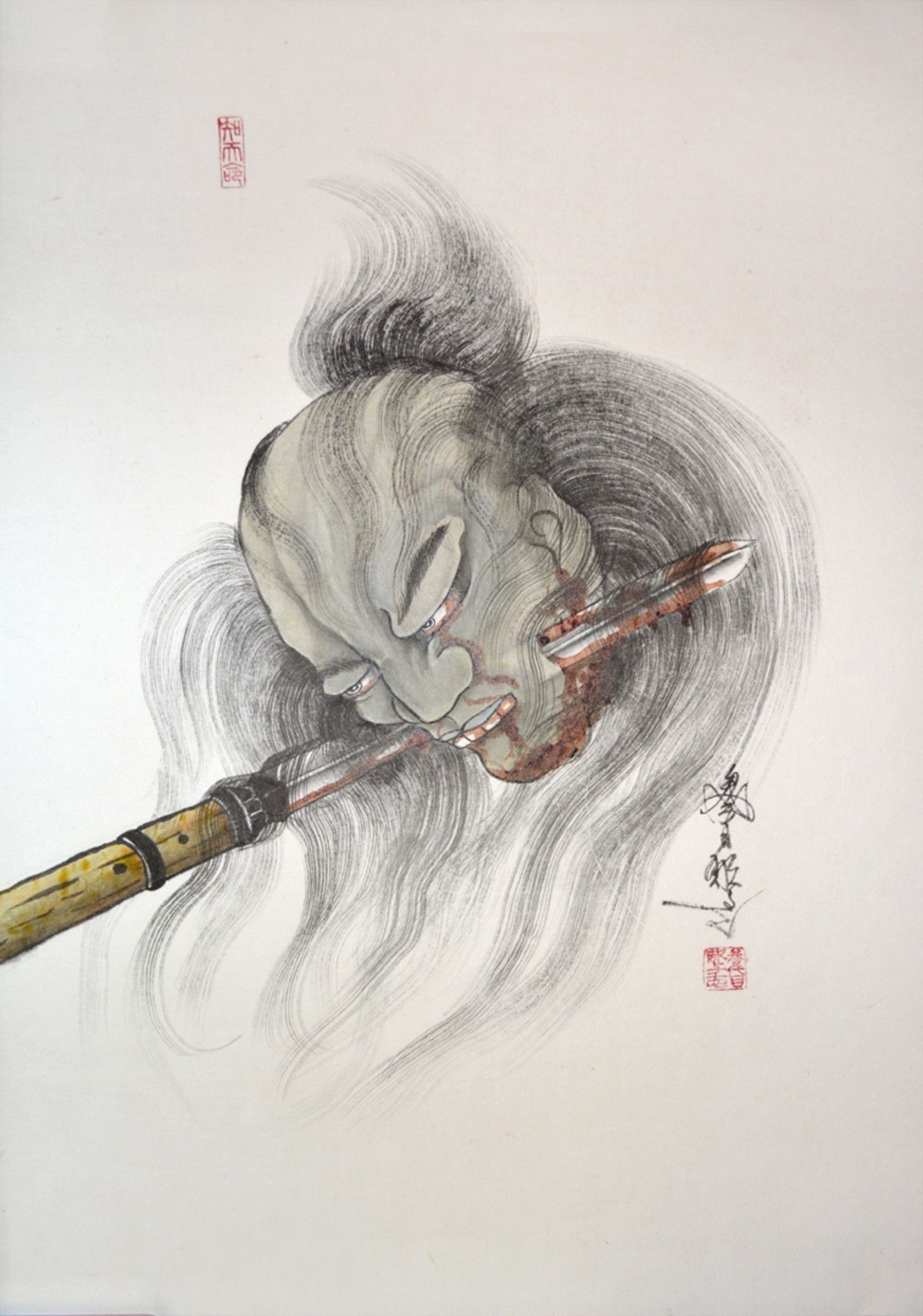

NAMAKUBI (SEVERED HEAD)

Namakubi in tattoo can be used to show many things, courage, a warning, respect for foe, or just as an image of no fear. Willingness to accept your fate and with honour is one for the messages namakubi is used for. A brutal image none the less, it is applied not as shock factor only, but as an element to the circle of life, for example-when taking a head it is done with respect for the person and that persons cause, but can also be used to show others the punishment if they are not living a truly righteous life.

Horiyoshi III, Namakubi - Speared.

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” Symbology.

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

Rogue with Nine Dragon Tattoos

1858. Toyokuni III/Kunisada (1786 - 1864) Japanese Woodblock Print

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

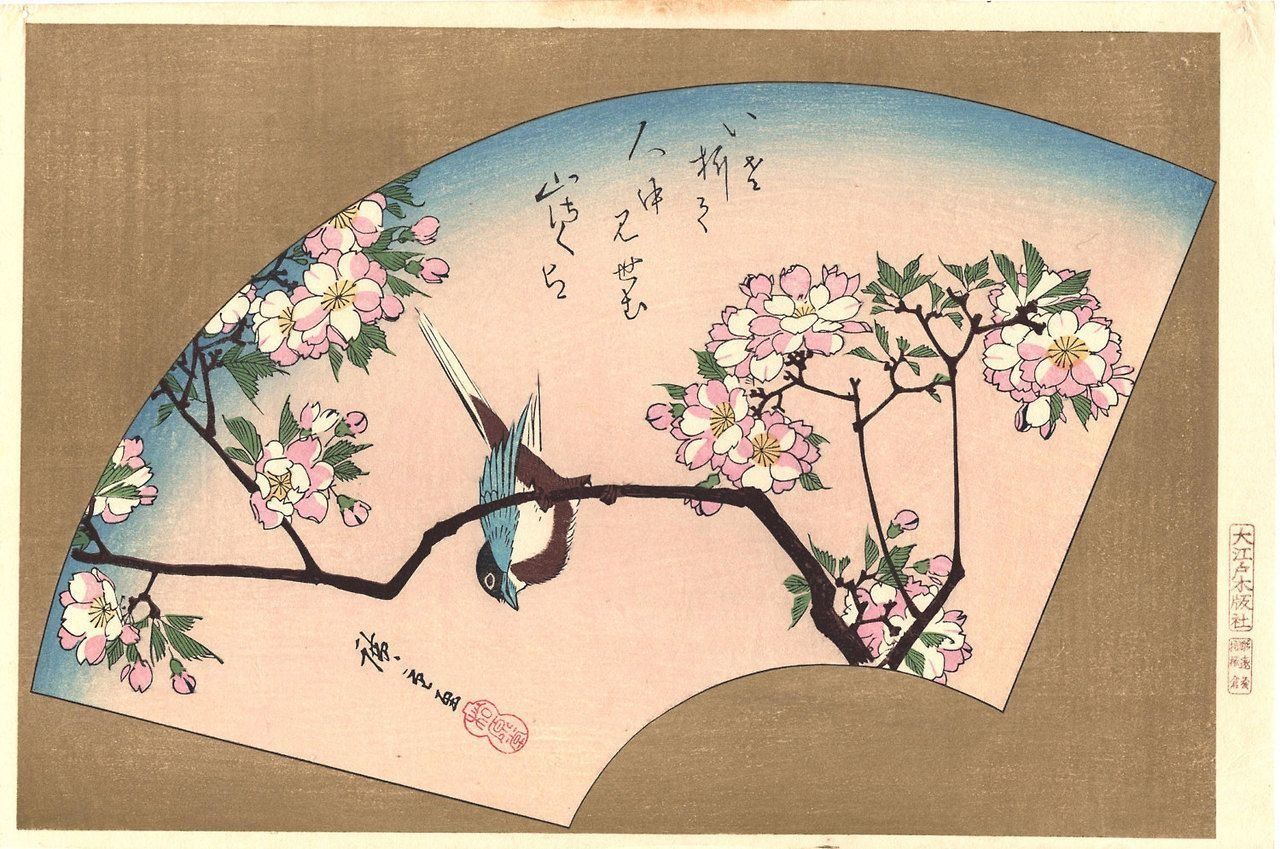

BOTAN (PEONY)

The Peony is considered the best of flowers and is known as the King of flowers. In short it means elegance and wealth. With it’s large and spreading petals, which are delicately curled at the edges, the peony has been called “the rose without thorns”. Although often depicted in tattoo imagery in deep red, it is today also cultivated in many other colours.

In the ornate, complex, and extensive body coverage that is typically involved in Japanese tattoos, it may seem as though entire gardens appear, but the floral repertoire of traditional Japanese tattoo is not as extensive as it might first appear, among the select flowers that are used is the peony, it is regarded as a symbol of wealth, good fortune and prosperity. In addition though, it also suggests a sort of gambling, daring and even a masculine devil-may-care attitude, quite unlike its character in the west.

Peonies

Utagawa Hiroshige II, 1866

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

MOMIJI (MAPLE LEAF)

One of the most popular backgrounds is the Japanese maple, a symbol of time passing, a symbol of the wind. the design often conveys the leaves as floating, carried on the wind or in the water. In Japan, it’s also the symbol of lovers. In some Japanese tattoo designs, canopies of maple leaves float over shoulders and drift over the torso.

A single leaf or a multitude of leaves are also potent symbols of regeneration and resurrection as they cycle through the seasons. Changing seasons are marked by the transformation of the leaves from trees. Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter are potent reminders of the circle of life, leaves are vivid reminders to us all of the life-and-death cycle of all living things. A tree losing the last of its leaves in the cold winds of autumn, to be stripped bare for the onset of winter has a poignancy that has long stirred the souls of poets, philosophers and men alike. The parallels of our own human lifetime are all too obvious. We could do worse than to meditate upon a rotting leaf on a damp forest path, often just a ghost of its former self. ‘This too will pass,” said the Buddha.

Maple by Sakai Hōitsu (1761-1828)

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

KIKU (CHRYSANTHEMUM)

This blossom is often portrayed as a symbol of perfection. The Japanese regard the chrysanthemum as their ‘solar flower’- the Japanese Imperial Family adopting it as their emblem and the Seal of the Emperor himself. The Emperor’s position is referred to as The Chrysanthemum Throne. The flower is depicted with petals radiating like flames from the sun, the centre of which symbolizes the Emperor’s status in the scheme of things. Longevity and joy are the attributes of both flower and worthy ruler. In Japan, the Imperial Order of the Chrysanthemum is the highest Order of Chivalry. Japan also has a National Chrysanthemum Day, which is called the Festival of Happiness.

Autumn is the season of this flower and in China the chrysanthemum is a symbol of Taoist simplicity and perfection. A time of tranquillity, completeness, and abundance following the harvest. Since it blooms right into winter, it may also symbolize the ability to mediate between life and death, between Heaven and Earth.

Although traditional Japanese tattoos give an initial impression of chaotic complexity and a seemingly infinite number of design elements from which to choose, such is not the case, In fact, traditional Japanese tattoos tend to be drawn from a smaller set of symbols – primarily the cherry blossom, the peony, and the chrysanthemum.

From its identification with autumn, when it blooms, to its association with other fall qualities such as rest after the harvest season, and eventually to periods of quiet contemplation, the chrysanthemum has moved naturally into symbolizing a time of withdrawal and retreat. Even the word itself, in Chinese “chu” or “ju”, sounds like the word for “wait” or “linger.” Other sound-alike made the chrysanthemum ideal for messages of congratulations or good will and wishes for long life.

However, its symbolic link to longevity and happiness in Japanese culture may be draw more from its actual appearance. Circular and symmetric with numberless rays that flow from its centre, the chrysanthemum fits into the class of symbols that we recognize as solar. As a sun symbol, it immediately links to representations of life and longevity. While the cherry blossom of spring references the brevity and bright beauty of our transient lives, the chrysanthemum plays the opposite role in tattoo artwork. It is the flower of fall and of fullness, symbolizing not only a long life but a complete and happy one as well.

ukurokuju (God of Wealth and Happiness) Depicted Through Flowers: Auspicious Chrysanthemums, Utagawa Hiroshige II, 1818~1860.

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” Symbology.

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

Rogue with Nine Dragon Tattoos

1858. Toyokuni III/Kunisada (1786 - 1864) Japanese Woodblock Print

Until the Edo period in Japan (1600–1868) tattoos, world wide, were done with marks and symbolism rather than imagery. It was in Japan, in the Edo period, that “decorative” tattoo began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The Traditional Japanese Tattoo “Irezumi” is the decoration of the body with mythical beasts, flowers, leafs, and other images from stories, myths and tales. The impetus for the development of the art was the progression of the woodblock prints and notably the “hero’s heavily decorated with Irezumi”. Wearing Irezumi is an “Aspiration” to life’s goals.

Woodblock artists began tattooing, using many of the same tools for tattooing as they did to create their woodblock prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, unique ink known as Nara ink, or Nara black, the ink that famously turns blue-green under the skin, which is the true look of the tattoo.

There is academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth who wore expensive Irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that Irezumi became associated with and proudly worn by the firemen, dashing figures of bravery and roguish sex-appeal who wore them as a form of spiritual aid and protection, thus the revered “Suit of Nine Dragons” to give power over wind and water.

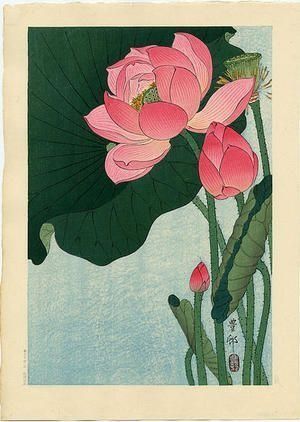

HASU (LOTUS)

Lotus flowers are amazing and have strong symbolic ties to many Asian religions, especially throughout India and the lotus has become a symbol for awakening to the meaning of life. The meaning varies slightly between myth to myth of course but essentially religious traditions place importance on the lotus flower.

In modern times the meaning of a lotus flower tattoo ties into it’s religious symbolism and meaning. Most tattoo enthusiast feel that the a lotus tattoo represent life in general. As the lotus flower grows up from the mud into a object of great beauty people also grow and change into something more beautiful (hopefully!). So the symbol represent the struggle of life at its most basic form.

Lotus and peonies are flowers that are very popular among Japanese tattoo artists and they make a great compliment to Koi tattoos. Ironically enough, the two, koi fish and lotus flowers can often be found in the same pond in front of a temple. The Koi fish is a symbol typically for strength and individualism.

Ohara Koson

Ohara Koson, Flowering Lotus, Ca. 1930s.

Color Symbolism

F.A.Q.

More information about Japanese tattoo symbology and tattoo design elements meaning can be found in our

BLOG

from The Symbolic Way

“Symbols speak where words fall silent.”