We Loved the article and interview by Hunter Oatman-Stanford for

CollectorsWeekly so we are happy to share it with our readers, keeping all the links attached.

Epic Ink: How Japanese Warrior Prints Popularized the Full-Body Tattoo

By Hunter Oatman-Stanford

— October 24th, 2017

In the late 1820s, when artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi debuted his stunning new series of warrior prints, Japanese culture was well into a period of flux. Since around 1615, after the ruling Tokugawa family established their headquarters in Edo (the former name for Tokyo), the country had been set on a course of rapid urbanization and isolation from the global order. The private wealth of Japan’s thriving merchant class fueled the emergence of the so-called Floating World—shadowy urban districts devoted to nightlife and entertainment—and a host of media chronicling its hedonistic delights. In response, the country’s leaders passed laws to curb the spread of illicit activity and establish new standards of decency.

“Tattoos were for the fashionable urban commoners, not usually people of a high social level.”

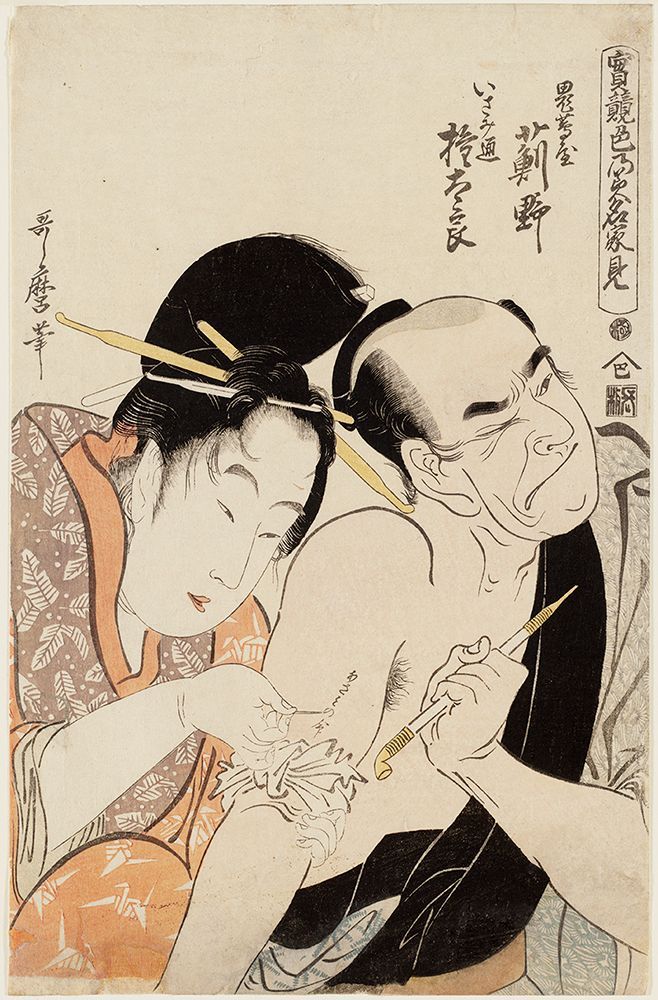

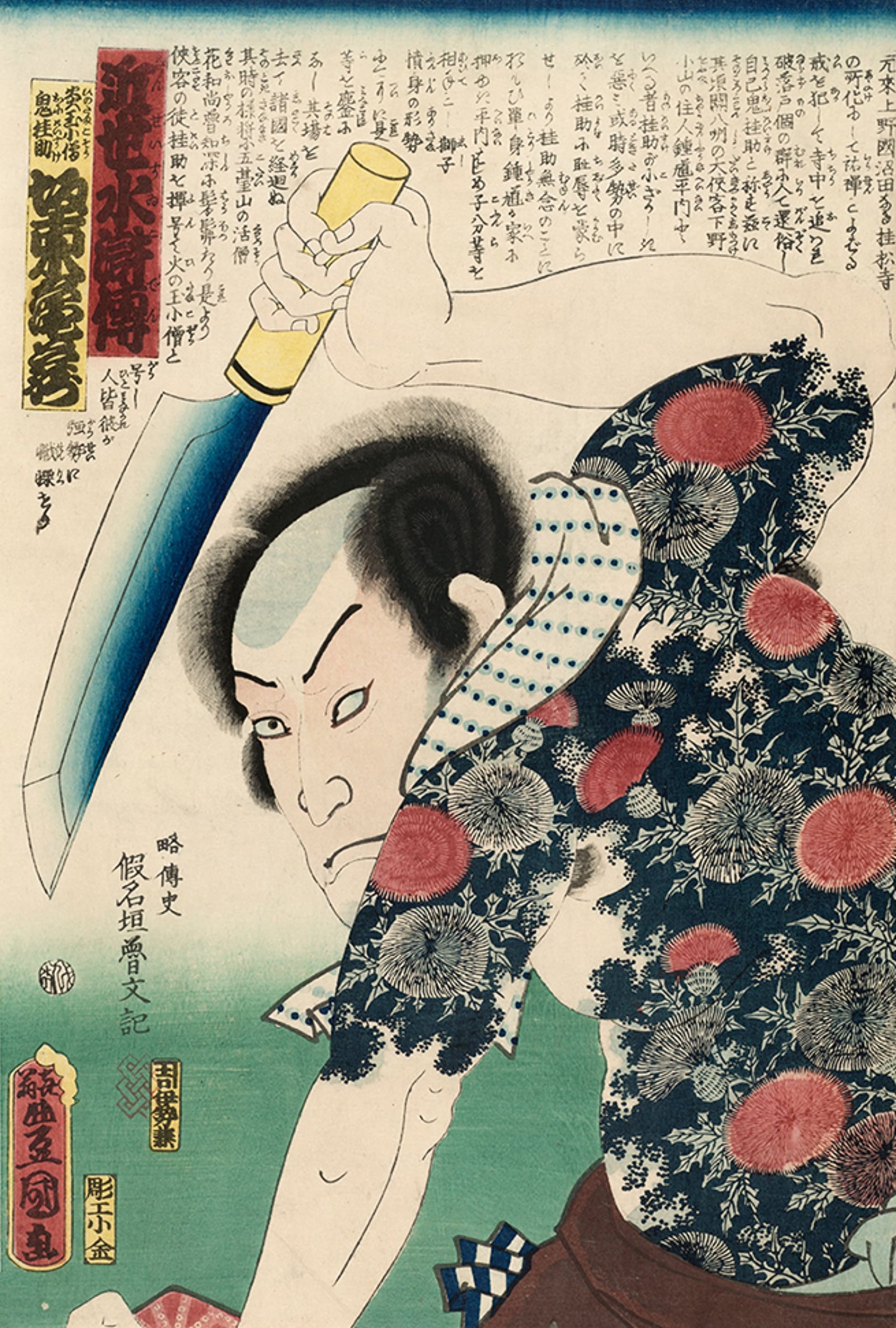

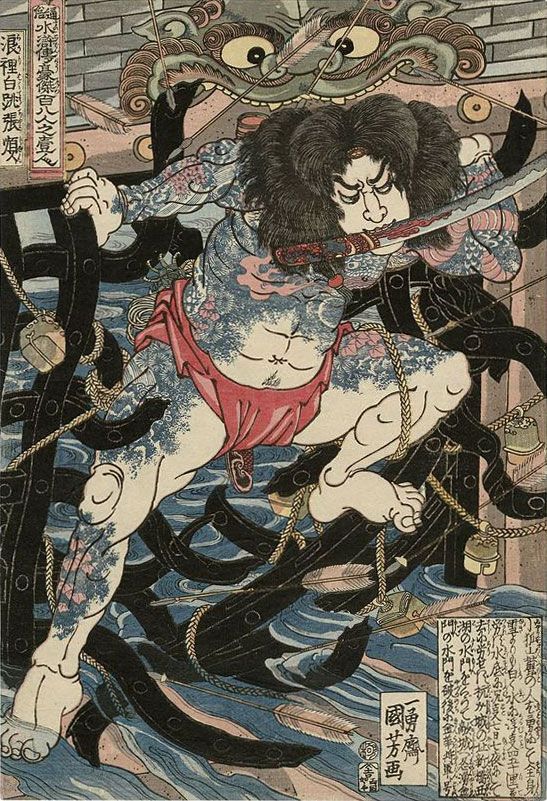

Kuniyoshi released his action-packed illustrations, inspired by the characters of a popular Chinese martial-arts novel, amid this social turmoil. But unlike previous illustrators who stuck closely to the text, Kuniyoshi made a key change, adorning several of the story’s heroes with elaborate, large-scale tattoos. In doing so, he merged fantasy and decorative art to create a breathtaking new style of body modification. By transforming a few brief mentions of tattoos in the source material into a vibrant feature of his prints, Kuniyoshi produced a cultural touchstone that remains influential more than a century after his death.

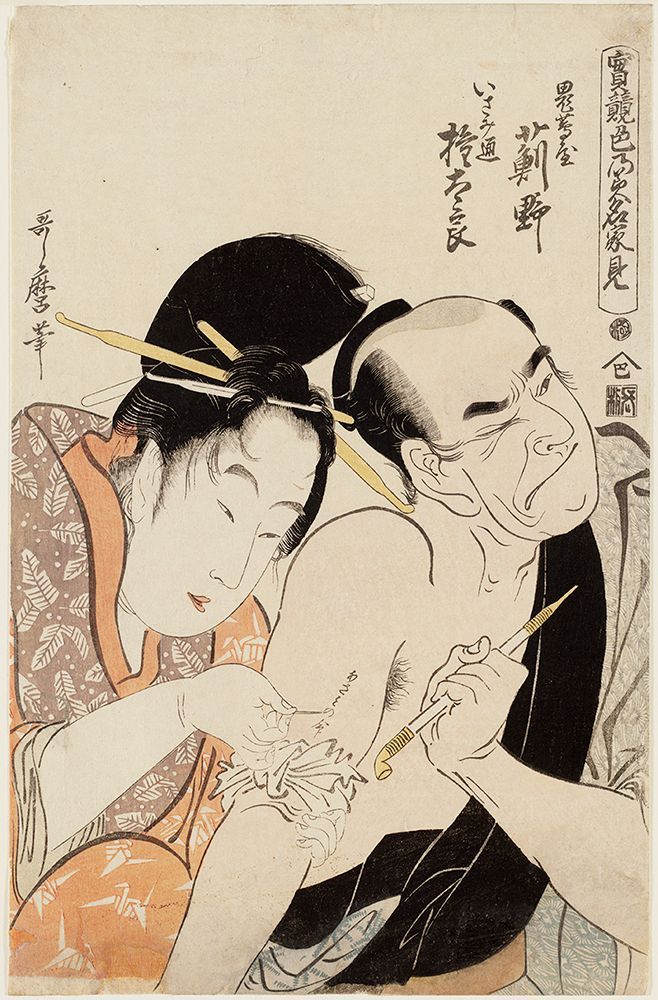

Tattooing existed in Japan well before the Edo Period: Small tattoos of words or text were sometimes applied when a person took a romantic or religious vow, or were forcibly given to criminals to remind others of their transgressions. But as with other areas of Japanese life, the disruptive social shifts of the Edo Period transformed tattoos from basic lettering into a complex art form.

During the 1790s, government censors began cracking down on books and prints to discourage works that celebrated the vices of the Floating World. As a direct result, publishers focused on fictional stories with historic settings and lots of action, including the 14th-century Chinese book Shuihuzhuan, or “Water Margin,” whose Japanese translations had already been popular for decades. As the mythical tale of Chinese vigilantes living on a mountain surrounded by wild marshland (hence the book’s title), Water Margin, or Suikoden, as it was titled in Japanese, fit perfectly into this trendy new genre of historic fiction. The novel’s first Japanese translation appeared in episodic segments between 1757 and 1790, and instantly inspired other adaptations.

Similar to the 20th-century Marvel Universe, authors and illustrators repurposed characters and plotlines from Water Margin for a variety of media over the course of several generations. The story’s most famous translation, A New Illustrated Edition of Water Margin, debuted in 1805, with original text by Kyokutei Bakin and illustrations by Katsushika Hokusai. Though conflicts between Bakin and Hokusai forced the publisher to pause production, more than a decade later, Utagawa Kuniyoshi was inspired by this version to create his series, “108 Heroes of the Popular Water Margin,” released to great acclaim in the late 1820s.

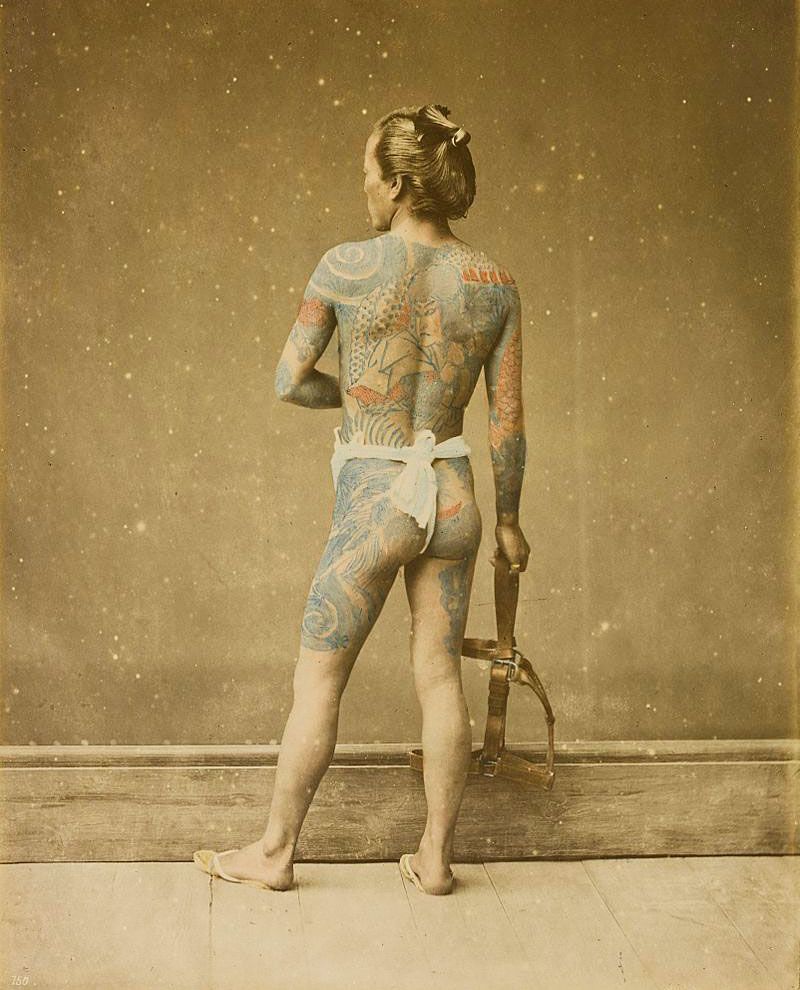

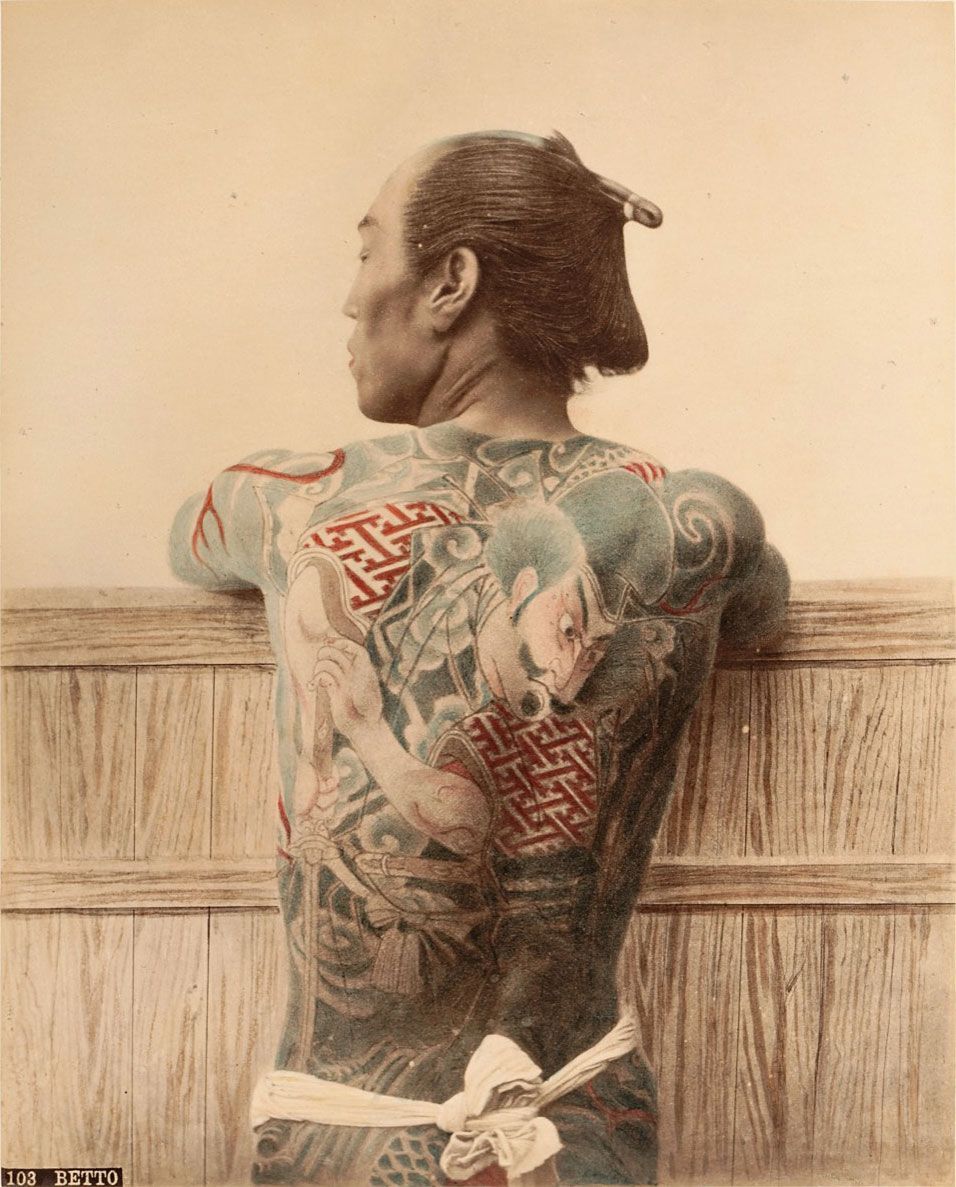

As Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, curator Sarah E. Thompson explains in her book, Tattoos in Japanese Prints, Kuniyoshi took a few references to the tattoos of four characters and made them a prominent feature of his elaborate artwork. “In the illustrations of Chinese editions of the book, which Hokusai followed closely in his own versions, the tattoos are relatively simple line drawings,” Thompson writes. “Kuniyoshi, however, created extravagant, complex prints-within-prints, filled with color and action.” Of the 75 different heroes Kuniyoshi included in his unfinished series, 15 were depicted with large pictorial tattoos. Many of these tattoos include imagery drawn from the natural world—waterfalls, lions, snakes, peonies, monkeys, octopi, fish—while others show fantastic creatures and gods. Though earlier Water Margin prints had been popular with the public, Kuniyoshi’s series was such a massive hit that it established a entirely new genre of printmaking—musha-e or warrior prints—and made its tattooed subjects into style icons for many fans.

After the Water Margin illustrations launched Kuniyoshi to fame, he continued producing artwork of the ukiyo-e school, or imagery of the Floating World. Many of these prints featured kabuki performers, a group of all-male celebrities that often donned fake tattoos for certain roles, and such portraits served to increase the visibility and popularity of bodysuit-style tattoos. It’s unclear how much Kuniyoshi’s art was influenced by actual tattoos, rather than simply his imagination, but regardless, his inked protagonists inspired countless copycat characters, artwork featuring tattooed subjects, and real-world tattoos in the decades following.

“Not only were the tattoos that Kuniyoshi designed for the heroes copied in real life, but also the heroes themselves became the subjects for tattoos,” Thompson writes. We recently spoke with Thompson about the appearance of tattoos in Japanese art and the flowering of their real-world counterparts.

Collectors Weekly: What are the first records of tattoos in Japan?

Sarah E. Thompson: The earliest records of any tattooing going on in Japan are actually from Chinese history books of the 3rd century C.E., which include accounts of travelers who went to a place that is most likely Japan. One of those mentions that people had tattoos in that country. But the large-scale pictorial tattoos that we know today seem to have originated sometime around the beginning of the 19th century, and it’s not exactly clear how it happened. There was a shift from small tattoos—either given as some kind of mark to punish criminals or when someone made a vow to a lover or a deity—to these big, gorgeous pictorial tattoos that look like some kind of bodysuit. Small tattoos that symbolized a vow would be more acceptable, especially if they were religious, but in general, tattoos were for the fashionable urban commoners, not usually people of a high social level.

Collectors Weekly: What led to the emergence of the so-called “Floating World”?

Thompson: The Edo Period, which was roughly 1615 to 1868, is often described as the early modern period in Japan. During that time there was a major shift from a feudal society, in which your position was determined by birth, toward a more modern type of society, where your social status is mainly a matter of how much money you have.

Theoretically, the official class system was divided into four social classes, according to the neo-Confucian ideology of the rulers. At the top were the military rulers or the samurai, and the next most important were the peasants, because their labor was essential, and then the artisans who made useful things. The lowest of the four classes was the merchants because they didn’t do anything except shift money around. But in practice, the rich merchants were often better off than the poorer samurai.

However, there were legal limitations to what you could do with that money: If you were not a samurai, you couldn’t be involved in government or travel outside Japan, and even travel within Japan was somewhat restricted. So there were quite a lot of people with money to spend, and they spent it on this popular culture in the Floating World, which was a general term encompassing all the urban pleasures—the kabuki theater, the legal brothels, restaurants, fashion stores, all kinds of things. The name Floating World described this world of transient, ephemeral pleasures.

Collectors Weekly: What visual records do we have from this period?

Thompson: We have quite a lot of visual documentation from woodblock prints and book illustrations, which were created by the same artists. The pictorial woodblock prints were actually an offshoot of book publishing, which became a big business during the Edo Period. The Japanese had been printing for a long time, though it had mostly been done in the Buddhist context. But during the Edo Period, you have this increase in urbanization and the population who could be defined as middle class, plus a rise in literacy rates. In the bigger cities, there were enough people who could read or at the very least had friends who could read to them, so there was a growing market for popular reading matter.

“Firefighters were very likely to have tattoos, often of dragons because they’re water creatures, so it was an implicit prayer that the dragons would rain on the fire.”

The earliest printed materials were mostly versions of classical literature, but pretty quickly publishers started getting authors to write stories about new subjects like the Floating World. In terms of woodblock prints, those were a spin-off from book publishing roughly around 1680, when they started selling single-sheet pictures as a separate product line.

People would pin or glue these prints to their walls and throw them away when they got tired of them. Fortunately for us, some people liked them enough to save their prints even if they weren’t really meant to be saved. People who did keep them often pasted them into albums—they were glued together, perhaps with prints back to back, and then bound together. You could also do it in scroll form, or as an accordion-folded type of book. That’s the way a lot of things survived.

Collectors Weekly: What were the subjects of these print series?

Thompson: What was written about in books and what was illustrated with prints typically went hand in hand. Especially in the 18th century, there were a number of works of fiction about what went on in the Floating World—love affairs between rich playboys and courtesans, that kind of thing. There was also a substantial amount of nonfiction, travel guides, how-to books, and classical literature in addition to popular literature. There were critiques of courtesans and kabuki actors, maps, all types of things.

In the 1790s, there was a bit of a crackdown with the Kansei Reforms, a set of laws that tried to make people less frivolous and more moral. Moving into the beginning of the 19th century, there was a tendency for popular authors to avoid stories about present-day life and look at more distant history instead. As you know, Water Margin, which was Kuniyoshi’s first hit series, was based on a translation of a Chinese novel from several centuries earlier. But Japanese authors also wrote other adventure stories inspired by it, spin-offs set during different periods of Japanese history. To a large extent, the authors were trying to create something that would sell well and was still acceptable to the government.

Collectors Weekly: Were there illustrations of large pictorial tattoos before Water Margin became popular?

Thompson: Yes, there are a few, which is interesting. Some people think that Kuniyoshi’s Water Margin series started it all, but I think there were large-scale tattoos being done before that. Interestingly enough, much of the evidence is in early prints by Kuniyoshi himself. He had been active as an artist for 10 years or so when he finally had this big hit with the Water Margin series in the late 1820s. But if you look at some of Kuniyoshi’s own works from earlier in the 1820s, you find images of men with those types of large tattoos.

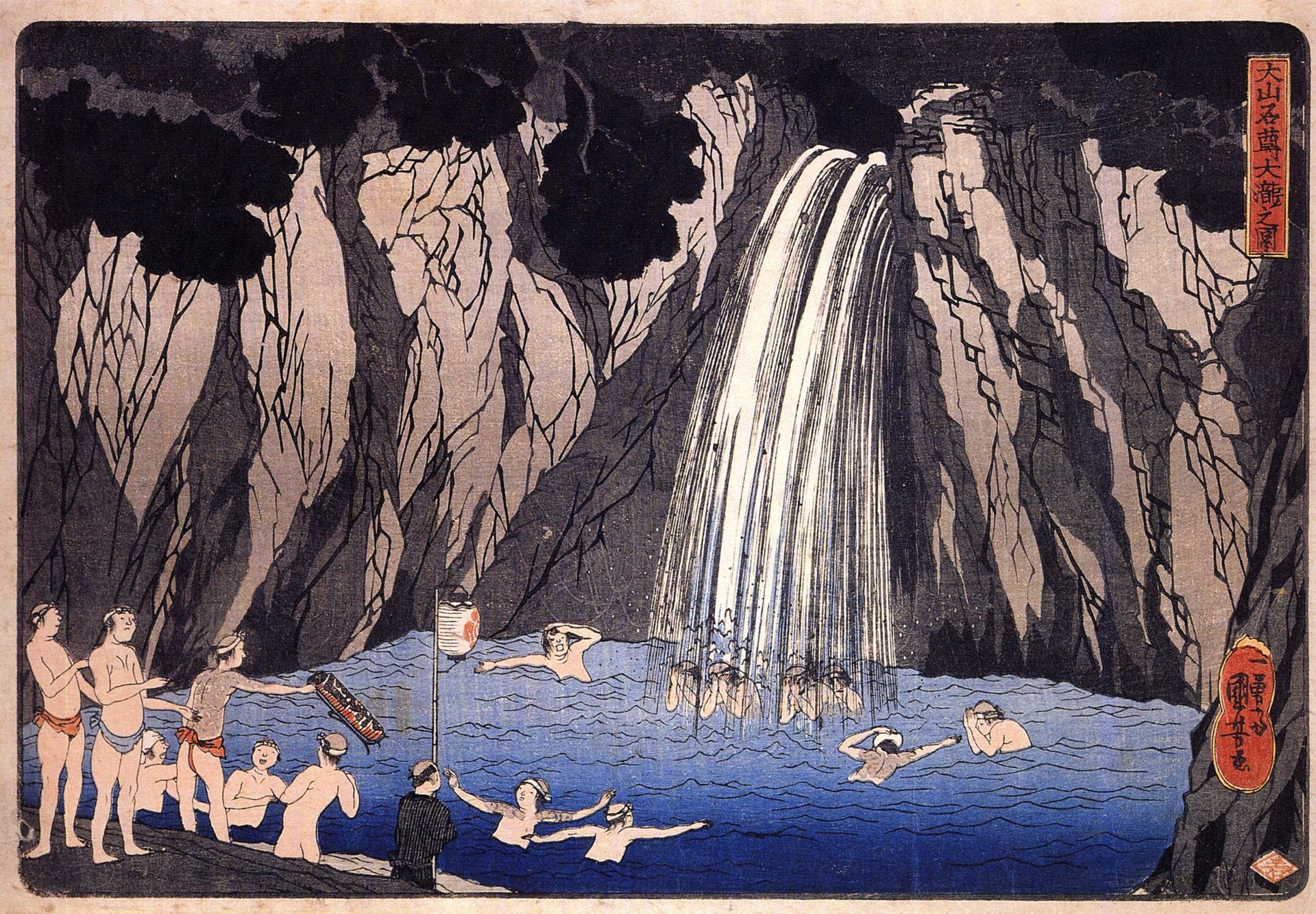

In one of the early Kuniyoshi prints in the MFA’s current show, there’s a little inset showing a fishmonger cutting up a fish and he has tattoos. We can’t date that exactly, but judging from the style, it looks as if it’s from the early 1820s, a few years before he did the Water Margin series. There’s also a well-known triptych where Kuniyoshi shows a group of men making a pilgrimage to a sacred waterfall, and when they get into the water, many of the men have tattoos.

I think the trend for pictorial tattoos had started already, though we could credit Kuniyoshi with taking it to a new level of artistic value and making it something that would really last. But I’m still collecting evidence for this.

Collectors Weekly: How was the Water Margin story absorbed into Japanese culture?

Thompson: There had been Water Margin translations going back to the 18th century, and you see references to it sometimes in print, but it seems to have been something that only Sinophile intellectuals knew about. Then there was this popular translation in the early 19th century, which was illustrated by Hokusai. That seems to have made the story really famous, although there’s a bit of a gap between the first part of the translation coming out and the time when Kuniyoshi did his prints in the late 1820s. Hokusai’s original illustrations did include tattooed characters, but he drew the tattoos as fairly simple outlines, rather than the elaborate designs Kuniyoshi illustrated.

Most of Kuniyoshi’s heroes were not shown with tattoos and that seems to reflect reality—even when tattoos were very popular, they were still only popular for a minority of people. These images were supposed to represent 12th-century China, but we don’t know much about tattoos at that time, other than the fact that they did exist because they are actually mentioned in the original book, Shuihuzhuan. Four of the 108 heroes were specifically said to have had tattoos, and Kuniyoshi put tattoos on 15 of them.

Collectors Weekly: What types of tattoos did Kuniyoshi depict?

Thompson: Lions and peonies were very common, and this gave the warriors a mildly exotic look since, of course, there were no lions in Japan, or in China either, for that matter. You see them in Buddhist art because that ultimately came from India where there are real lions, but for the Japanese at this time, they were almost imaginary animals used as symbols of courage.

Dragons were also very popular, and other mythical creatures like giant snakes. Often a hero is depicted fighting a monster. There’s another story that crops up a lot about a diving woman who steals a jewel back from the Dragon King, and you see her swimming along, being chased by water creatures. Occasionally, you see something like a courtesan in her full elaborate costume, parading down the street, but that is a bit unusual. Usually, it’s something more violent, something with a lot of action.

Collectors Weekly: Did Kuniyoshi’s series spawn a lot of imitations?

Thompson: It was his Water Margin series that made the warrior prints, or musha-e, a major new genre of subject matter—right up there with beautiful women and kabuki actors. Just a few years later, Hokusai did the same thing for landscape prints when he brought out his “36 Views of Mount Fuji” series, which was also a huge hit. Kuniyoshi was great at the warrior prints, and he continued to be the main artist doing them, but other artists created them as well. Kuniyoshi himself brought out a second series of Japanese heroes and put tattoos on some of them, even though it wasn’t necessarily historically appropriate. So their depictions aren’t only connected to the Water Margin.

Collectors Weekly: During the Edo Period, do you think tattoos were more common in prints than in reality?

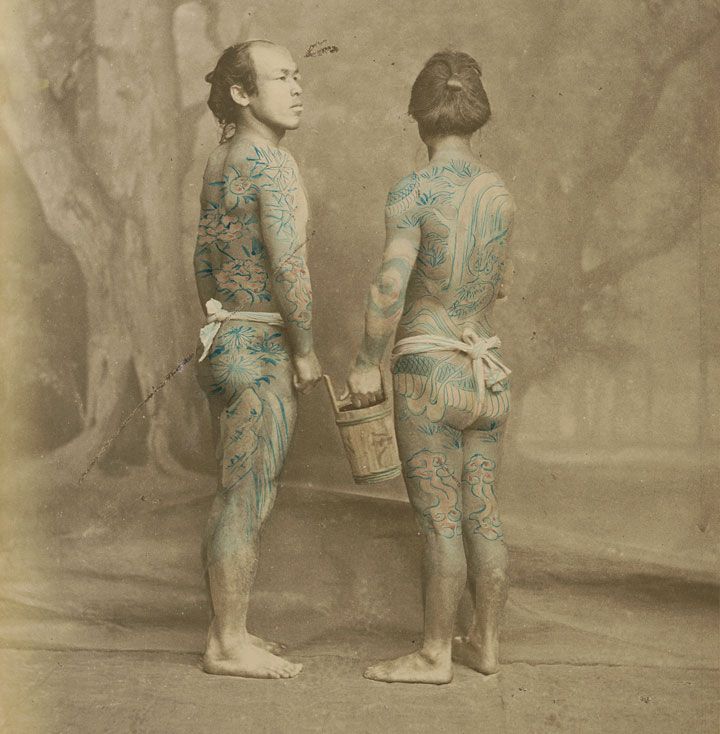

Thompson: Possibly. It’s hard to say. By the time you get into the later Meiji Era and foreign tourists were running around photographing people, there certainly were a fair number of tattoos. They’re typically seen on working-class men who did physical labor that involved stripping down when the weather is warm—porters, palanquin carriers, horse groomsmen, firefighters, those kinds of jobs. Firefighters were very likely to have tattoos, often of dragons because they’re water creatures, so it was an implicit prayer that the dragons would rain on the fire.

Collectors Weekly: Were women ever portrayed with large tattoos during this period?

Thompson: Somewhat to my surprise, no. I haven’t found any direct evidence of women in the Edo Period, or even in the following Meiji Period, being tattooed. If you look at present-day movies and manga and so on, historical Edo-Period stories often include women with tattoos. But looking at material actually from the period, I can’t find any evidence for women with tattoos. The closest thing I could find was a Meiji triptych that supposedly shows tattooed women, but it’s actually kabuki actors who were all men.

My impression is that women were not getting tattoos at that time. I think it was probably around the beginning of the 20th century that women started getting tattoos, although, at that point, it was illegal anyway, so only women in certain underground social circles were doing it.

Collectors Weekly: Why was tattooing Japanese citizens made illegal after 1868?

Thompson: That was around the time of a major push for modernization in Japan, and it looks as if the Japanese government thought tattoos were old-fashioned and kind of embarrassing. The upper class had never had them anyway, so the people who were running the country probably thought, “Ugh, those working-class men with their tacky tattoos. The foreigners will think we’re all uncivilized!” Something along those lines seems to have been the rationale, though I don’t think there was any official explanation.

Collectors Weekly: Did tattoo artists continue practicing after these restrictions were in place?

Thompson: Yes, on an underground basis. Despite the fact that Japanese officials restricted tattooing because they were worried about what outsiders would think, real foreigners actually liked the tattoos. Although getting tattooed was illegal for Japanese citizens, tattoo artists were permitted to tattoo foreigners. Many tourists who came to Japan wanted to get tattoos—apparently even royalty like George V of England and Nicholas II of Russia, who received tattoos while in Japan. In port areas like Yokohama, there were legal tattoo shops for foreigners, though I’m sure the same tattooers were doing work on Japanese clients secretly.

The restrictions were finally removed in the early 1950s under the American occupation after World War II on grounds of freedom of expression. The argument was that in proper democracies, people should be able to get tattoos if they want.

For more on the emergence of pictorial tattoos in Japan, check out Sarah E. Thompson’s book, “Tattoos in Japanese Prints.”

All Tattoo Projects

Other Posts

Ready to start your tattoo project?

We do NOT do walk-ins. ONLY private appointments which really easy to schedule. Please learn the process and request your consultation.